Thursday, October 31, 2019

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

Monday, October 28, 2019

Strolling in Reel Time along Fuyamachi

The next installment of the Kyoto Streets series, at Deep Kyoto:

http://www.deepkyoto.com/strolling-in-reel-time-along-fuyamachi/

On the turntable: Average White Band, "AWB"

Sunday, October 27, 2019

Sunday Papers: Samuel Johnson

"Those who do not read can have nothing to think, and little to say."

On the turntable: Bauhaus, "... And Remains"

Saturday, October 26, 2019

Wednesday, October 23, 2019

Wasshoi Kenka Tomodachi

During my 25 years in Japan, I've been quite proactive about getting around to see most of the country's interesting corners. And in this current climate of overtourism, I feel lucky to have visited places before they were overrun. Recently, my attention has shifted to visiting festivals, particularly, the smaller, more localized ones, where Yamato Damashi still reigns.

So it was I finally get to a festival I've long been trying to catch, Nada Fighting Festival, held every October at Matsubara Hachiman Shrine in Himeji. From the station I spy a few food stalls, the primary position occupied by a guy selling kebabs. I wander through the stalls, then cut across the grounds of the shrine. It is crowded but not packed, allowing room to maneuver around the spectators and the teams standing around their respective portable omikoshi shrines. The latter seemed keyed up, and I take care not to jostle anyone, particularly as I'm the lone foreigner in sight. There is a bottle-neck near the main gate which we all try to funnel through. A couple of the participants are trying to hurry along, one lightly but incessantly placing his hand on my lower back. Walking across these grounds I feel like I'm in the most dangerous place in Japan.

Then I'm out. Every second story window of the houses adjacent to the shrine are full. A woman in a wheelchair sits beyond the outer gate, unable to see the main events but satisfied simply with the vibe. Older men stand holding long staffs of bamboo, some with these origami-like orbs at the top, the colors representing a particular team. The young men strut about, most of them drunk. It seems that the common denominator of anyone over 20 is the can of beer or Hi Chu in their hand. (The type of alcohol drunk differed by team, and I'd back the highball guys over the Asahi guys any day.) No matter the color of the happi, the face above it is a bright red. The fundoshi they all wear are white, at least for now. The youngest participants are high-school aged probably, as 16 is the lower age limit. They too look drunk, though drunk on nerves. And the youngest of the young boys are similarly ready for the fight, with their plastic swords and cap-guns. Above it all are the ever-constant drums, an ominous warning, pumping us up for things to come.

These are the Japanese that most of the West doesn't see, infatuated as it is with the salaryman, the geisha, the otaku. Strolling past are the farmer and the fisherman, truck driver and laborer. The stereotypical politeness is in little evidence today. With this level the testosterone, and all that bare buttock and leg, I find myself in Donald Richie's world, a world I had thought long gone.

The teams are constantly shifting, and it is hard to find a good place to stand. I finally settle in behind a few spectators, all old-timers, figuring that they have had decades of experience sorting this out. The bigger portable shrines squeeze out from the shrine, pulled by two dozen men who show incredible strain on their faces. Once they are through, smaller shrines race out to the main torii arch and back, one team in particularly showing remarkable speed. These are the fighting shrines. After that initial burst of energy, the three teams settle for a while at the center of the open space outside the shrine. We wait, and wait, and wait some more. But I like this, as the intensity of anticipation begins to coil within each of us. Then release, the three shrine crashing together with a great clack!, as the surrounding crowd raises both arms not in the expectant banzai, but in order to capture the action with their smart phones.

The toppled shrines are righted, then move out for the long climb up to Mt. Otabi, where a smaller crowd awaits. And the largest shrines again begin to move, their teams long quiet after their initial boisterous entry. The entire event has taken less than an hour.

The crowd is hesitant in their disbursement, as if worn down from the earlier cathartic release. Most linger around the food stalls, but I return to the train.

This whole day has been initiated in a way by Jordan, who enthused about the festival after attending twenty five years ago. This area Himeji will always remind me of him. I need to change trains in Akashi, not far from where he trained in aikido, the catalyst for his moving to Japan all those years ago. The city's castle grounds are near the station, so I allow myself an hour to climb up to the site of the former keep before returning to catch my train.

As I ascend the great stone steps I realize that I'm still carried the heavy weight of grief for my dear departed friend. But with grief, I feel there is no reason to fight. Better instead to throw my arm around its shoulders and invite it to share a beer.

On the turntable: The Jam, "The Jam at the BBC"

Sunday, October 20, 2019

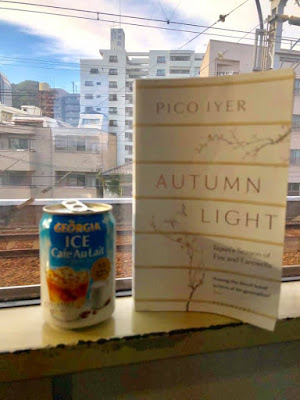

Sunday Papers: Pico Iyer

“It's in the spaces where nothing is happening that one has to make a life.”

On the turntable: Violet Indiana, "Choke"

Friday, October 18, 2019

Wednesday, October 16, 2019

Monday, October 14, 2019

Friday, October 11, 2019

Disseminating Tracks VIII: The Hustai, and Beyond

The wind of last evening promised, and the weather this morning delivers. We leave camp in a light rain, the first we've seen while in country. Luckily, we follow a surfaced road for most of the journey. I pass the time by finding interesting-looking mountains out on the horizon, and wait for the inevitable roadside ovoo that honor them. We pass through a series of little towns, each one more wild, wild west than the last. Buzzards perch lined up along the fence surrounding a rubbish tip. The built-in joke that all the petrol stations are called "MT."

The rain stops. We eventually turn off the tarmac onto a dirt path, no doubt surprising a western woman squatting nearby to pee. It is a rough track out to the ger camp, where we're to have lunch. I don't know it yet but by morning it will become my least favorite of the trip. I was thinking how much I was going to miss this ger glamping, but a noisy trio of drivers talking half the night make me appreciate the upcoming hotel bed. Not to mention that there are a good number of unsavoury looking characters simply hanging about. There are plenty of tourists too, including one bitchy Englishwoman who is particular nasty to me while in the queue for the buffet. Despite the hardships, I find myself missing the desert.

After lunch we trace the river through an elongated series of hills. We stop suddenly, for eagle-eyed Tulga has somehow spotted a small group of horses nudging their way along the cliffs that overhang the valley. These are the famed Takhi wild horses, the only true wild horses left on earth. My color blind eyes have a little trouble distinguishing their coats from the brown hills behind.

We move onward, crossing a stream whose length is foretold by the long line of trees adjacent. The mountains above take on the fantastic conical shapes of extinct volcanoes. It truly is a dramatic yet peaceful place, and it's easy to see why the ancient Turkic people settled here long long ago. Their graves remain, a long line of stones mimicked the earlier trees in the way they stretch away toward the horizon.

We meander back toward camp on the other side of the mountains that had shaded us on the way in. A young deer has fallen into a ravine and seems unable to move, but we leave it be, so as not to make worse the situation. Then we spot the horses, closer than before, and we drive up toward them. They graze oblivious to us, still a safe distance away. There appear to two groups, following the lead of their respective alphas. Suddenly we notice another male, a massive elk with magnificent horns. He too is leading a group of his own. Amazing how this entire menagerie appeared out of what had seemed to be empty space.

We get another even closer look at two other groups during the drive out. They are just off road, and we quietly stalk them to get good photos. Like the other night, the horses are moving single file toward somewhere, but being wild, every place is home. We watch them a long while, until the fading light tells us that we too best move.

The number of tourists at the camp hinted that Ulaanbaatar is close, and the land grows more and more cluttered until we are indeed in town. By good luck, the International Horseback Archery Championships are the following weekend, so we drop by the watch the riders train. It is a strange setting, just above a cluster of ger that look puny beside what had been a film set for a recent Chingiss Khan biopic. The Mongolian horsemen look relaxed, almost as if they have no horse beneath them and are merely gliding bowlegged across the land. A trio of bowmen practice in front of a group of targets, even spinning around to fire backwards. It is easy to see how their forefathers conquered the world. Many of the foreigners by contrast look big and clumsy. In their demeanor too. Due to his English skills, Tulga is corralled into interpreting for the organizers, and some of the Europeans attempt to rebut this and assert their own will. The Asians in turn have said nothing, and look more favorable for it. The highlight of course is when we, all the while standing in our matching polo shirts and commenting on the proceedings, are asked by one German women who we were.

We head toward city center, for our last afternoon as a group. Midway there, we drop into a traffic jams as bad as any I've ever seen. Apparently the city's 1.7 million inhabitants have one million cars. The city is trying to curb their use by restricting say, those whose license plate ends in "1" from driving on Monday, those with "2" from driving on Tuesday, and so on. Residents get around this by simply changing plates. Quite crafty, these Mongolians.

We eventually arrive at the Winter Palace of the Bogd Khan, and wander awhile through the temple and grounds. The Russian-style house is the highlight though, filled with exquisite furnishings and decor. As we go, I wonder which room housed the 13th Dalai Lama, who took exile here after fleeing the British invasion of Tibet in 1903.

As the traffic jam made us miss lunch, we decide to simply do dinner early. I'm pleased that Veranda is the venue, as I'd wanted to at least grab a coffee there, in this funky little jazz and Euro-themed cafe overlooking the Chojin Lama temple. After a fortnight with the diet we've had, we all go a little overboard with the ordering, the wine in particular. Thus it is in high spirits we thanked our team, and part officially as a group.

Thus freed, LYL and I dart over to buy my horse-head fiddle, then rest awhile. Our number is down to four when we meet for a farewell drink on the rooftop restaurant of our hotel. The owner is a funny fellow, almost Russian in his demeanor. He takes us to the helipad above, and we admire the lights of the city. He tells us that a few days before, he'd been angered to find an array of snipers lying along one edge, acting as security for Putin's visit in the city square below. He told them, "I don't give a shit who is coming, this is my roof! You need to ask my permission!"

The Spirit of the Mongol lives on...

On the turntable: Hank Mobley, "The Best of..."

Wednesday, October 09, 2019

Disseminating Tracks VII: The Orkhon Cradle

We aren't on tarmac very long before our tires embrace earth once again. We're cutting laterally across a valley, with dozens of mice scurrying out our way. An eagle sits off to once side of the road, bemused, until one of us raises a camera and then he's gone. We stop for a pee break, beneath a hillside covered by sheep, though oddly only on one side. A motorcycle pulls up, an old man and his young granddaughter. He sits on the ground, sharing a smoke and a chat with our drivers. Bilgee hops on the old man's bike and races around like in an advert for those short-lived Bronson motorbikes. The old man seems completely unperturbed.

We make another impromptu stop, at a lone ger set at the curve of a broad valley. Tulga had apparently chosen them at random, dropping in uninvited with eight other guests. But the hospitality immediately appears, namely in the form of khumiss, that alcoholic, fermented mare's milk that I'd been wanting to try. It is lighter than expected, a bit like unrefined sake. I hope for another sip, but sadly the bowl doesn't come around again. (I do refuse a second helping of sheep brain, scraped raw direct from the skull by a grinning Bilgee.) The young family here are very friendly, with an infant, and an older boy. The wife is strikingly attractive, and looks ten years younger than her 27 years. She also seems to be the only one doing any work, ever on the move, yet moving with an unhurried calm.

We all file out to watch her and the boy milk the horses. A few dozen are tethered along a single rope, the young foals a little skittish at the newcomers. A few of us get a chance at riding, and when mine turn comes I feel surprisingly comfortable in the saddle. The day is warm and beautiful, the location beyond picturesque. I think how nice it would be to do a horse tour in Mongolia, enjoying a passage of days as nice as this one.

Another couple turn up, relatives apparently. One of the men offers to demonstrate lassoing one of the newer, unbroken horses. It takes a few attempts, but they finally get him. Bilgee, ever the maverick, wants a ride. It bucks and leaps, and he's only on for a handful of seconds before he goes bum first into the dust. He'll play it off laughing, but later on I notice a large scrape on one elbow. Tough guy Charles Bronson indeed.

We continue along the valley, at one point weaving through a large flock of black and white sheep, like making one's way across a chessboard. Tarmac comes and goes, then we cross a stream at the head of the Orkhon Valley, which is supposedly the pastoral home of Mongolia's oldest people. Our ger camp sits along midway down the valley, isolated and with a good view from its position on a rise. We expected to leave again after lunch, though are delayed slightly by an intense wind storm that comes from nowhere, It is kind of exciting to sit in one's ger during such a storm, wondering if the entire thing will make like a UFO and take flight.

We eventually drive further into the Orkhon, above its broad valleys flecked with trees. At one point the river makes a dramatic series of turns, white water racing below the hilltop from which we admire it all. Not far from here is Temeen Chuluu, a collection of graves and deer stones commemorating a Turkic people, going back to the 3rd C. BCE. It is a peaceful place, the jagged stones like the sails of old ships, sailing toward the gentle hills behind. The mountains above are tree-covered and home to bears. We linger a long while here, but no one feels in any hurry (though I do feel a tinge of regret that we didn't get to visit the Tovkon Khiid monastery somewhere in the hills further out). I wander down to the river's edge, here a mild flow across the grasslands. Horses graze just the other side. You can almost envy the dead spending their eternal rest here.

We disembark the vehicles midway home and walk an hour or so back to camp. Tulga lingers behind, probably to allow us the chance to navigate, to get a sense of the challenges the nomads would have experienced navigating a rather featureless landscape. Horses too are on the move, walking single file to wherever they'll spend the night.

We spend ours at Ursa Major. Being an eco-camp, there is no electricity or running water. As such, there are no showers, but we are brought hot towels, carried in those wicker baskets best known for steaming Chinese bao. I take up the offer to get my hair shampooed, just for the experience. Then I return to the quiet of the approach of evening.

It's a large camp but there are only a few other guests. As is the case in most camps, the evening meal is western, and this one even has basilico squirted across the plate, served up by a man with a Native American dream-catcher tattooed on one forearm. We linger long after dinner, before the staff gestures that they want to go. But we still have wine, so we all return to one ger, to tell ghost stories as the wind again kicks up outside. The fire in the stove of our own ger takes the edge off the cold, but I am not long in enjoying it as the wine and the long day nudge me quickly into sleep.

I awake early to read out front of the ger, warming myself with the coffee I'd made. I could sit here all day and watch the herds of animals moving back and forth across the Steppe. A group of horses comes up the hill, accelerating as they descend. I wonder what inspires these movements. Does one animal just suddenly go and the rest follow? A majority of their group crosses the dirt track without hesitation, but an old timer coming up far to the rear, moves across gingerly. Then they all suddenly stop and begin to graze. The little ones keep running around in circles, at play.

Kharkhorin comes up suddenly, or at least what is left of it. The Soviets had attempted to build a small city here, now a ruin of tall buildings at the center of town, the side of one laid open like a nasty wound. The rest of the city (or more aptly, town), is low and residential, residences aligned in rows, alternating in square blocks or round gers, like a game board where the players can't agree on the rules.

Erdene Zuu Khiid holds court at the center, as you'd expect from the Mongolia's best known monastery. From her previous visit three years ago, LYL remembers the area as run down and abandoned, but today about a dozen small shops stand shoulder to shoulder across the carpark. Originally built in the 16th century to declare Tibetan Buddhism as Mongolia's state religion (an act that also saw the first use of the title of Dalai Lama), the monastery was badly neglected during the Soviet years. Back in the 1990s, I nearly got involved in an opportunity to help restore it to its former glory, though in a further example of impermanence, my plans fell through in the end.

The site is vast, though the current buildings on site are all on one side. A massive ger of 45 meters circumference once held court at center, though now all is covered by grass. The three main temple buildings are of various shapes. Monks are active in one of these, as a priest leads them through their pre-meal prayers. We sit awhile to listen, then move to a neighboring building to recieve blessings for a safe journey. The biggest temple buildings had once been the spiritual heart of the site, but today now function as a museum. Ironically the scrolls and Buddhas are far grander than those in the active temple itself.

We move over to our camp, and lunch. It is quite large and busy, and one can't help but feel a sort of tourist vibe here. Kharkhorin being a tourist town, this makes sense. And in this particular case I hardly mind, as it offers electricity, points for charging devices, and most importantly, the first hot shower in five days. If ger had windows, I would be able to see former sumo grand champion Asashoryu's more polished and posh-looking camp just across the river, large oval-shaped ger of bright white. I imagine a great deal of yen must flow through there.

In the afternoon, we visit the museum. As LYL has been here, she begs off to go visit some shops selling silk. I do a cursory look around the exhibits (enjoying particularly the maps, the ruins of the old kiln, and the diorama of the historical Kharkhorin), then Tulga frees me to return to Erdene Zuu, to see a few features my guidebook has told me I've missed. It feels good to be on my own for a while. I pass a pair of young monks carrying brooms dawdle and laugh as they go. Behind the row of shops, a small child defecates in the dust.

The wind is high when we all regroup. We wander out to the stone turtle that marks where Chinngis Khan's son, Ögedei set up his capital. A few of the remaining stone columns were visible beneath a massive platform, but little else. We'll visit another turtle atop a hill nearby, stopping on the way to admire a large phallus at its base. Legend has it that the phallus is a reminder to the monastery monks to control their sexual impulses, but imagine it is a fertility symbol for a good harvest, nestled as it in beside a stream that undoubtedly goes on to water the crops further on.

Not far from the turtle is one of the largest ovoo I've seen, piled high with horse skulls. As I undergo the obligatory three circuits around it, the wind is growing in intensity. It has felt like autumn for days, but this wind from the north promises winter. The Buddhists are right, change is ever-constant.

On the turntable: Art of Noise, "Dreaming in Colour"

Monday, October 07, 2019

Disseminating Tracks VI: Desert to Steppe

The sun rises on us, its warmth creeping across our little plateau, moving from ger to ger. It isn't long before the trucks are ready to go, and we pull away from one of the most remote places on earth.

It proves difficult to route-find in the glare of the rising sun. For the first time our drivers need to rely on "Mongolian GPS," stopping at a lonely ger to ask directions. There are hundreds of sheep and one little girl, maybe two-years old, eating from what looks like a bag of marshmallows.

We move steadily toward a wall of mountains to the north, which marks the provincial border. Just before reaching them, we follow the windy, roller-coaster like road across the conical hilltips. Then we drop again, racing along a dry riverbed. We come finally to the wall, and amazingly the drivers know the way, turning right. With a bit of winding around, we find our way through.

A series of rock canyons have sandy bottomed beds and boulders piled up as if they were assembled there. We speed past a small abandoned camp, abandoned for the time being anyway. It has a couple of large corrals, some overturned water troughs, and a few baobab trees. A pair of ovoo still remain up on the hills above. The gods will keep watch.

Then long flatlands, with not a thing on the horizon, even more sparse than yesterday, which at least had small blooms of shrubs. Long triangular hills appear in the far distance.

The eye tries to make sense of the empty landscape, placing in it things it is familiar with. I begin to see what I consider prehistoric rock formations, ancient, spiritual places, but in those are just the things that the earth has offered up. My eyes are used to traversing the deserts of New Mexico, and perceive where I expect there to be towns. But of course here there are none, simply pools of haze in low lying valleys.

And then some small shrubs begin to arise, and with them camels. They are the tallest things on the landscape, although their shadows make them appear even taller. To the west, a shimmering mirage reflects the peak of Ikh Bodg. Then we roar down into the town of Bayanig at high speed, a banner of dust trails trailing behind. To a person watching in the town, this would have looked reminiscent of the approach of invading horsemen of days old.

We stop to allow our drivers to refuel, and poke around the town's sole shop. I'm delighted to find what is labelled as Craft Beer (but later on I can barely drink it, for god knows how long it has sat moldering on the shelf). A pair of big motorcycles are in front of a restaurant next door. The riders are Dutch, and are intending to cut their trip short as they are finding they have the wrong bikes, too heavy for these dirt roads. I decide to rewatch Ewen MacGregor's trips when I get home.

Our camp is not far out of town, sitting alone at the base of the nearby mountains. It is a small camp, and there are no other guests. After the obligatory afternoon rest, we set off after the day sheds her heat. We are in search of ibexes, but find none. Instead it is we who scramble up and down the jagged rocks. We sit a long while here, gazing out over the land, and spilling out stories when they occur to us. It has been a magnificent day, moving through a constantly changing landscape, as if someone is flicking through a photographic album, turning the page every fifteen or twenty minutes. The magic of the land seems to have won us over, and we are no hurry to move.

When we do, it is to al fresco dining, the evening far too pleasant for us to wrap ourselves in the felt walls of the dining ger. When the stars come out they are of a number I've never seen, and the magic takes another form. There are constellations, satellites, and few planes. Most of all there are the meteors. There is also a sudden bright flash, which both puzzles and dazzles. It is a night of which myths are born.

In the morning, we again squeeze our way through what appears from afar to be a solid wall of rock. Into the flatland of the other side. The highest thing on the landscape is a dead camel. Our vehicles race one another along parallel tracks, another Mongolian superhighway. They shift and swerve from one to another in a beautifully choreographed dance of steel and dust.

The landscape has changed again, to that of Arizona; boulder-filled valleys and mountains jagged like the Superstitions. But I am returned to the present by the ovoo, many are just off road, in line with a distant peak. A truck carrying the broken-down components of a ger overtakes an ancient Lada. A traffic jam is caused by thick flocks of sheep, a dog acting a traffic cop. Stones line the hilltops, and mice race across the tarmac made hot by the noonday sun. Horses shade themselves under a bridge.

Just outside of Arvaikheer (which I jokingly pronounce as I hear it: "Ah Fuckit!") we stop at a horse monument, which is a ring of tall concrete horses standing before a shrine decorated with Buddhist deities. Nearly out of sight behind is a long line of horse skulls leading to an ovoo. There are a number of people here, families, dressed up for photos on the kid's first day of school.

Then into the city proper, and in a city, lunch can only be hot pot. Later, as we walk through town to the hotel I feel people staring, which could be because I'm foreign, or it could because I'm absolutely coated in dust. Tonight will be the first time in over a week that we'll sleep in something not circular (provided we don't drink too much). The room is lavish, probably built for high-ranking party members back in the Soviet days, the furniture garish and too many in number. The feeling of style over substance continues at dinner, taken at what is called an Irish pub. There is no Guinness, but there is an German Bock, welcome after a week of light (though tasty) pilsners. Our meal is taking far too much time, so we cancel half of it.

We'll take a night stroll through town, over to the central square (there's always one) which is rife with young people just hanging around, and little children proving a hazard in their funky little motorized cars. Tulga treats us to a quad-bicycle ride around the square, so LYL and I take a lap, trying not to run over any of the little daredevils. We'd earlier seen families dressed up to celebrate the new school year, and the night has just that feel, the hint of cool in the air dictating summer's end.

On the turntable: Bob Marley and the Wailers, "Exodus"

Friday, October 04, 2019

Disseminating Tracks V: Dinosaur Country

We start our long drive into the desert with a prayer stop at a large ovoo with a good number of ibex horns wrapped around wood and stone. From here our vehicle literally glides across the sands, skating through a low opening in the dunes. It is a pretty white ride, and in hindsight I should have given thanks at the ovoo that I'm not at the wheel.

The higher desert beyond is dotted with saxaul bushes. (A bad joke is made about their being called this since the plant sucks all the available moisture from the earth.) Their numbers thin out, and the landscape suddenly becomes green. We sneak through a broad dusty pass on the Altai, where a shepherd gives water to his flock. As our group mills about, stretching their legs, I make a quick climb up a hill above, and am surprised to see a small cluster of ger hidden in the valley on the other side.

Toward midday, there is a further surprise, that of a tarmac leading to a small town. It's amusing that someone would decide it was needed, as it simply vanishes again on either side of town. This is the last stop for trucks heading into China, which is a mere pass away. There are only a few vehicles today in Gurvantes, a two-horse town with a name right out of northern New Mexican. There are a number of ger around the perimeter, and a few brick buildings at center, as well as a small and door-less toilet shack that proves to be one of the grottiest squat-drop loos in the world.

We all file into the town grocery store to stock up on snacks and for Tulga to arrange our box lunch. The shop appears to be composed of just two aisles: one with alcohol and one with sweets. It makes sense that there's not any real meat here since that would taken off the hoof, though there is a cooler at the back, filled with offal and an extraordanant amount of chicken legs. It did seem somewhat incongruous to see the cartons of milk in the freezer toward the back.

Stocked up, we await for someone to show up and open the warehouse nextdoor where they store the cases of water. (If I ever publish a collection of my Asia travel pieces, it'll be titled Waiting for the Guy with the Key.) After a short drive out into the desert we stop suddenly for our picnic, literally in the middle of nowhere. We settle in for what we all expect to be another long drive, but then a surprisingly short time later, we arrive at camp.

Overall, this camp at Naran Daats will prove to be the least comfortable, due to its rock-hard beds and lack of hot water. (Apparently there was some, but not for me.) I try to find more comfort by folding all the duvet layers under me, which sort of works but I shiver through both nights. But such hardship always makes for an interesting memory, and after all, isn't that we paid for?

But I liked the camp's isolation, sitting at the corner of a broad ledge, overlooking a narrow canyon of white rock and red earth, that must flood wildly in wet weather, begetting a rich panorama of wildflowers in spring. A single family seemed to run the place, and I wondered at the young boy, how boring he must find it. (I find out later he spends most of the year at school in Gervantes.) The patriarch has long ago made peace with it all though, and most often he could be seen sitting before his ger, silhouetted beautifully against the landscape, his three-legged dog ever at his feet.

We go out to explore, climbing past an an ovoo and a makeshift spring filled with cans of beers for the night. At the top is a pagoda that has one of the Tibetan Tara's carved into the side. This adds even more holiness to the natural cathedral through which we walk. After traversing the

canyon rim we descend, crossing to the the far walls where Tulga finds us the spine of a dinosaur, jutting from earth. Fossils such as this continue to appear and disappear as the soft earthen walls of such canyons give way in heavy rains. Thus for a good guide, such discoveries are always new.

We'll find another set of bones the following day, shattered and calcified into pieces of fallen stone. Searching nearby is a small group of French, a family that I met earlier, as they passed us in their old Russian van. I remembered in particular their son of perhaps 12 years, who looked so delighted at finding dinosaurs, right down to his Jurassic Park T-shirt. The heat of the day would prove too much for the poor thing, as back in camp I'd see him walking back and forth to the loo, his mother alongside, who didn't look so good herself.

We spend the relative cool of morning exploring Khongoryn Els, called Mongolia's Grand Canyon by the locals. To me it is more Canyon de Chelly, extending laterally, rather than having the massive scale and depth of the Grand. Standing at the cliff's edge I remember well my descents into both, a descent I recreate today, first down onto a massive sand dune tucked into one corner, then downward still onto the stone floor. We move beneath the towering red walls, which narrows eventually into a slot canyon. The path out is along a dry riverbed, pushing at one point through dense reeds.

Lunch follows, in the shade of a small oasis. Tulga decides to wait for the heat to drop before we undergo our aforementioned dinosaur search (which also provides the ironic parallel of a good look at a massive lizard scaling a rock wall). Most of the group goes to the trucks to doze, but I decide to stretch out beneath a small juniper. As I lie there, I feel a connection somehow with the timelessness of nomads, and an simple understanding of how to survive out here. In the day's heat and the frigidity of night, beneath the flawless blue canopy, beneath the magnificent burst of stars.

I believe that we all share something similar on the day, in our own way. After dinner we sit awhile nursing Georgian wine in the gazebo at the center of camp, basking in the quiet and the awe, until the spirit takes us and for some reason we all begin to sing songs by Leonard Cohen. From Montreal to Mongolia. Why not?

On the turntable: Jean Michel Jarre, "Oxygene Trilogy"

Wednesday, October 02, 2019

Disseminating Tracks IV: Camel Country

Not long after breakfast, our digestive juices are swirling around as our vehicle bounces across the desert. We follow established tracks, though occasionally we lurch sideways to take another one. I think about how hard this kind of driving must be on the drivers, the constant diligence of the eye, the constant jostling of muscle and bone.

We all get a reprieve at the Khavtsgait Petroglyphs, dating anywhere from 3000 to 8000 BCE. A short steep climb brings me to the top of a bluff, dotted with jagged black stones that had been here long before that. Tulga shows be the first two or three petroglyph sites, them releases me to seek more on my own, I meander up and down the northern cliff face, the now familiar glyphs jumping out in the morning sun. Ibex are most prevalent, one in particular having been drawn in exquisite detail. The thin paths are lined with goat droppings, looking like a musical score. In the brush, the grasshoppers are beginning to awake, clicking like those old sprinkler systems from the 1970s. It is pleasant to wander these heights, the hills behind me defining the border with China, and everything else stretching away to the flat line of the horizon.

It isn't too far from there the flaming cliffs of Bayanzag, where we catch up with the Korean tour groups. I walk out to the edge of a narrow spit of land, allowing myself for a moment the feeling of being out here totally alone. The features of the landscape speak of having once been part of the sea floor long long ago, before they dried up to give the dinosaurs room to roam.

Lunch follows, at a ger camp run by two young women. One of them greets us to offer milk, drunk warm from a hand-carved earthen bowl. She is dressed in traditional garb, yet the rest of her hints at a certain nonconformist cool, with her cop sunglasses and hair tinted that orange shade which the Japanese used to do in the 90's before they got the chemistry right.

We move on over the flat earth. Despite the remoteness, animals are never far away. Camels graze in the most remote sections; cattle prefer to stay closer to small water stations. We'll occasionally part like Moses large oceans of sheep strewn across the road. Tracks constantly multiply and divide. At one point in the low hills we lose the other vehicle, but then quickly unite, its familiar boxy shape and accompanying trail of dust never difficult to spot.

Throughout the day, we make multiple stops, usually to pile out to look at some animal, or a bird swirling overhead. Eagles are most common, though a group of ibex moving toward the hills occupies us for a good while. As such, the long drives are never monotonous, as the land does its best to present its infinite charm.

The day ends at a busy ger camp. It has an old Western homestead feel, with a broad porch and long wooden benches in the dining hall. The visitors here seem divided into European adventure-types, and the more general Korean tourists. The latter will keep me awake late, as their drunken voices carry shrilly through the thin air.

I read awhile in the early dawn, coffee warming me as I sit on the chilly porch. Camels graze out on the desert, their shadows stretching them into oddly-shaped spindly beasts. The famous sand dunes are out to the south, rising along the base of the hills. And above, the long, low and jagged peaks that are the Altai.

We won't visit the dunes until the cool of evening. Tulga helps us occupy our morning with a walk out on the bluffs above camp. A small shack at their base provides the water and electrics, all running off an ancient car engine as generator. (I'll constantly be awed by the DIY approach that Mongolians have taken in order to live in these remote reaches. MacGyver could learn a few things.) A handful of horses graze amongst the crags, and further out, a group of English bicyclists pedal into the heat.

When the shadows of the camels begin to stretch in the opposite direction, it is time for our ride. But first we visit the camp of the camel drivers, sitting around the inner perimeter of the ger of a tough-looking middle aged woman who looks part of the earthen floor on which she so solidly sits. She bosses a couple of the younger men about, but truly dotes on her young son, who is stinted in size and unable to walk properly. The love they share is obvious in their interaction. A bowl of fermented camel's milk is being passed around, rich and thick like cottage cheese. I'm not particularly squeamish about the weird food of travel, but I worry a little about doing the following day's long bumpy car journey with a runny tummy. After all, there are no trees to squat behind.

We saddle up and move slowly through low scrub to the dunes. I miss the gentle ringing of camel bells, but at least the driver isn't playing incongruous music on his mobile like my driver in the Taklamakan last spring. But our's today is similarly disinterested in the whole thing. It is far more pleasant though to sit bareback, rather than be crushed into those uncomfortable wooden frames the Uiygurs prefer. We lurch gently along, laughing as our animals get bunched up. We take a pleasant meander through a shallow riverbed, as the non-riders in the group play paparazzi from the carved out cliffs above.

We disembark, the setting sun accentuating the sweep of the dunes as they cast lengthening shadows. Tulga points out a 'peak' further out, and allows us to find our own way. I take a long circuitous route along a ridge line, reached by a tough climb, the footing uncertain and ever shifting. Once at the top it is easier to move along the sharp lip of the dunes. The others further off look small as they each follow their own path. At one point I come across a horse skull, a reminder that some paths are shorter than others.

I find I've misgauged the length of the ridge, and as I race down into its trough I find that both my legs and my laughter are completely out of control. A sandstorm swirls around us for a minute or so after we regroup at the peak. Then the silence returns, yet another immensity in which to lose ourselves.

On the turntable: Art of Noise, "Moments of Love"

On the nighttable: Laurence Bergreen, "Marco Polo: From Venice to Xanadu"

On the nighttable: Laurence Bergreen, "Marco Polo: From Venice to Xanadu"

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)