Wednesday, December 08, 2010

It was 30 Years Ago Today...

My alarm radio turned on at 6:30 as it always did. I had it set to WPLJ, a station I'd discovered a few months before. During the summer, my musical interests were expanding, due in part to an older friend up the street who turned me onto The Ramones "Rocket to Russia" and the first album by The Clash. One September afternoon, I flipped my radio's switch to FM for the first time, and there were The Talking Heads doing "Life without Wartime." My radio never played AM ever again.

This particular morning, the first words I heard were, "New York has been living a nightmare." My brain switched on instantly, wondering what had happened. Soviet attack? Another blackout? Then I heard that John Lennon had been killed.

When I didn't get out of bed, my mother came in to see what was going on. I told her I felt sick. She brought me the thermometer to take my temp, which I then held in front of the heater until the mercury rose past 100. I spent the rest of the day with the music.

I've often had the experience where I really heard a band for the first time, despite having listened to them for years. It's happened with Dylan, with The Clash, and many others. Lennon's music too seemed to flow in and out of my life. One night in college, while watching the film, "Track 29," I was floored by the song "Mother,' it having special resonance as I was in the midst of an existential coming to terms with the fact that I'd been adopted.

In Japan, I found traces of Lennon all around, not really a surprise considering the Yoko connection. The tribute compilation, "Working Class Hero,' was in frequent rotation during my first year there. When I was in the national finals for Shorinji Kempo, standing on the floor of the Budokan with the other martial artists, my thoughts weren't on how far I'd come, or on the competition later in the day. My mind was instead fixed solely on "Holy Crap! John Lennon played here, man!" After my son was born, I'd often sing to him, "Beautiful Boy." That line saying life is what happens when you are busy making other plans took on a horrible resonance after Ken died.

Today, thirty years after Lennon's murder, I again find myself with the day off. I'll simply sit, dream my life away, and watch the wheels go round and round...

On the turntable:John Lennon, "The Lost Lennon Tapes"

Tuesday, December 07, 2010

Shoot Your "I" Out

I remember meeting a Shambhala kyudo practitioner a number of years ago. She was pretty adamant about the shot not being important, in keeping with the teachings of that particular style. And I get it, the Zen mind thing. Hey, I read Herrigel's (problematic) book too. But the way she went on and on, as if working on some actual shooting technique was wrong somehow, was getting frustrating. Now, I'm a pretty modest fellow, and held my tongue, but what I really wanted to say was, "Well, comparing your 6 months of practice with my 8 years, I'd guess you're far more proficient at not hitting the target than I."

On the turntable: JBT Scare Band,"Rumdum Daddy"

Thursday, November 25, 2010

5-7-5-0-1

It's funny, but emails can be a lot like haiku. There is a deliberate sparsity of language, yet the meaning can be inferred in multiple ways. Ironically, this sparsity leads toward experiential truth in the case of haiku, and toward perceived (and ofttimes misperceived) meaning in the case of mail.

On the turntable: Johnny Winter with Muddy Waters, "Live at the Tower Theater, 1977"

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Life Following Art

I am currently reading John Nichols New Mexico trilogy, which begins with The Milagro Beanfield War. I have read them before, during my first autumn in Japan, in an attempt to capture a little of that NM fall magic that I love so much.

I remember calling my folks back then and asking them to send the novels over. As they affixed the stamps to the package, it was like the release of water from an acequia, followed by a flood of books to follow over the next 15 years.

On the turntable: Grateful Dead, "1972 - 04 -14"

Thursday, November 18, 2010

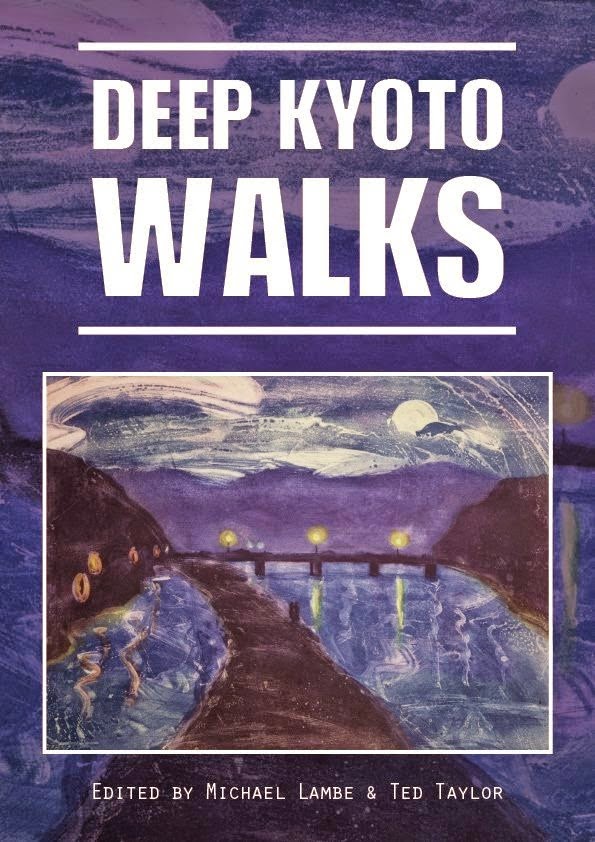

Bleeped Kyoto

Deep Kyoto's Micheal Lambe wrote a piece about the proposed and controversial Kyoto Aquarium. Originally published in the Kyoto Visitor's Guide, it was pulled after a phone call from city hall. While part of me wants to thank the city government for helping justify my move from their fair city, a deeper voice insists I speak out (yet again) against such shortsighted nonsense. So here is Micheal's piece. Read it, and decide for yourself.

Personally, I prefer to see my fish in the alleys of Nishiki...

Umekoji Park and the Kyoto Aquarium

Umekoji Park, a short walk north of Kyoto station, is an important patch of green in Kyoto city. Green spaces like this perform an important environmental function in a city: cleaning the air, and regulating the temperature. They are also beneficial for people’s physical and mental health. The park at Umekoji is very popular with the local community and is often used by sports enthusiasts and sports clubs from neighboring schools and universities. Others just come for a jog or to walk the dog. Families come here and children play. As I work nearby, I often go there myself, to throw a frisbee about, or take a stroll, or just to lie on the grass and breathe the fresh air. The grass, the trees, and the flowers here are very pleasant on the eye, and provide a rich habitat for birds and insects. You see a lot of smiling faces in this park...

I was shocked when I heard that Mayor Kadokawa had given Orix, a private company, permission to build a massive aquarium on a large chunk of this precious public land. Apparently, local officials believe it will bring in more tourists and revitalize the local economy. It’s hard to believe though that an aquarium can succeed in Kyoto; an inland city with no maritime associations! People visit Kyoto for its cultural and historical associations – not to see a large concrete box-like facility full of fish and deeply depressed dolphins! Surely it would make more sense to encourage businesses that take advantage of Kyoto’s existing assets; to restore machiya, improve existing museums and educate people about Japan’s traditional arts.

Incredibly, Orix Corporation claims that the aquarium will be an educational facility; teaching children about marine ecology. Here in this highly artificial environment, children will watch dolphins jump through hoops and be taught that wild animals are playthings to be kept in unnatural conditions for our own amusement. If you want to teach children about marine ecology, take them to the sea! Here in Kyoto we should be teaching them about the environment that is around them; the rivers, woods, and mountains and their indigenous species. This aquarium on completion will release 5,400 tons of carbon dioxide per year into Kyoto’s atmosphere. It is pure sophistry to claim it is an environmental facility.

Despite strong public protest however, the project is going ahead. Construction began in July and the aquarium is due to open early next year. I think it’s time that foreign residents and visitors to Kyoto threw their weight behind the local campaign to stop this terrible plan. Let’s tell Orix and Mayor Kadokawa that this isn’t what visitors to Kyoto want. If you agree with me please visit http://www.thepetitionsite.com/1/stop-the-kyoto-aquarium/ and sign the petition to “Stop the Kyoto Aquarium”!

On the turntable: Phish, "Rift"

Saturday, November 06, 2010

'Round Shikoku Day 14

I again didn't sleep well, due to the rooster crowing about four hours before dawn. I opened the blinds to the view of Kōchi city below, glittering under a flawless blue sky.

[...]

Temple 33 was quiet and free of people but for a lone man setting up a veggie stand off to the side. Suddenly there was a gentle cling-cling of those fairy bells, and withing minutes, three groups of car pilgrims showed up. In front of the Hondo, they all chanted in their own particular timing, as if doing it in rounds.

We moved away from the sea into farmland spreading out toward, and between, the hills. Passing one greenhouse, I distinctly heard what I thought was a Hank Williams song. We followed a small canal to Temple 34, whose courtyard contained a Kannon statue with a face of unbelievable softness and compassion.

It was a hot day so we took time for ice cream, and then again for cold tea in front of a cafe. We'd been pretty close to burn out, but rather than take a day off, we chose to instead do a couple of consecutive half days, less than 15 km each, taking our time. Nearing Tosa city, we met Rte 56, and crossed the long bridge over the Niyodo-gawa into town. I'd been craving a milkshake for a week, so was thrilled to see those familiar golden arches. But I'd chosen the only Mac in the world that doesn't have a milkshake machine. Those few minutes inside caused a bizarre reaction in me. All the parents scolding their children for no apparent reason, created almost a panic reaction in me, and I desperately needed to flee. I guess I wasn't ready for the real world yet.

We found solace in a quiet cafe closer to the town center. We needed food, but they only did two things: tea or coffee. We hemmed and hawed a bit, but finally settled onto brown velvet cushions rarely seen except for on retro film sets. There was only one other customer, but he left early, returning a few minutes later with some yōkan, kindly worried about our stomachs. The cafe owner herself also gave us some cake she'd gotten from another customer, then left us alone for a couple of hours. We relaxed and eased into peace.

Around 3:30, we made for Temple 35. A paraglider had launched himself off the peak at the perimeter of town, and was now spiraling above the fields across which we zig-zagged. The final approach to the temple was up the same steep mountain. Through the gate, guarded by eye-less Nio, we reached our refuge for the night. There was a tsuyado there, a lovely 6 mat room below the Kannon hall. After 5pm, the crowds left, and we had the grounds to ourselves. The buildings themselves were of great age, and to protect them was a fire truck perpetually parked in the corner of the parking lot. There was strange pagoda which you entered down a set of descending steps, leading you to an alter, small and candle-lit, then descending again to the exit, from above. I couldn't grasp the physics of it, and decider to leave it to Escher, expert on such things.

We were intrigued by the sign for the 'forbidden forest,' but left it alone, to instead sit at the edge of the hill and watch the full moon rise over Tosa. After dark, we alternated reading in the tsuyado, or taking walks, solitary but for the resident cat. As I lay down to sleep, my eyes returned again and again to the tall figure out the window. Amida, silhouetted against the moonlit sky.

On the turntable: Pearl Jam, "Lost Dogs"

Thursday, October 28, 2010

'Round Shikoku Day 11

The night before, two cats had been fighting beside the harbor, like a couple of drunken sailors. This morning, a handful of kites were swirling in the sky, as if churning the clouds in order to ring out the last remnants of rain. A trio of old men sit looking over the harbor, not speaking. The seawall is an impressive piece of work, built like a labyrinth to protect the boats and the town from the typhoons which return again and again. The men seem a type of chorus, and may be looking for a tempest of another sort --a tsunami. Stirred into motion by the recent Samoan earthquake, it is due on these shores sometime after lunch. As if this isn't enough, a typhoon is also on its way.

Temple 25 overlooks the harbor, up a long flight of steps that pass beneath a beautiful bell tower. Twenty-six isn't very far away, atop a low mountain like Temple 24. The trio are interrelated and hold an important place in the Kodo Daishi mythology. Apparently it was here that he'd engaged a tengu in debate, who, if I understood correctly the overheard explanation of a tour guide, may actually have been a foreigner. My own pet theory is that the tengu may have been a tree, as the forest is filled with twisted and fantastic shapes. Ironically, on the way down the mountain, my pack caught a tree limb, which broke off the trunk and crashed down a few inches to my right. Most of the wood was rotten (and now sprinkled across my clothes and pack), but the center of the limb was solid enough to have broken a bone or shattered my skull. It was a close shave, but somehow I survived the Tengu's mojo.

There is a small market where the trail meets the highway. We buy lunch here and eat while watching the sea. Next door is a whale-themed center, where the model of a cute looking cartoon whale stands grinning beside an immense harpoon gun. As I eat, I wonder what sort of message this place is trying to send.

When we shoulder our bags it begins to rain, a rain that won't cease for 24 hours. A car driven by a monk stops beside us, and it looks like he's about to offer a ride, but his wife seems to talk him out of it. They drive off. An hour later we're walking down the main street of Kawa, a fine mixture of old Edo and Meiji period buildings. It is a relief to be off Ole '55 for the first time in days. A helicopter is circling the town, on tsunami watch. The really heavy water is in the air, falling all over us. The world is gray, gray funemushi bugs like something from Giger's nightmares, dashing along the gray concrete walls. My mood too is gray and for the third consecutive day I begin to hope for a ride. But this time I really meant it. I was tired of walking and wanted to get on with it, but I wanted to keep my integrity and not deliberately flag a lift. Yet the cars kept skimming past, the rain kept hammering down.

Near dark, I stepped onto a bridge and took a few steps into calf-deep water. "This sucks!" I yelled at nothing in particular. There was a machine shop nearby, so I ducked in, pouting at the rain. It didn't seem to notice, coming down as hard as before. As we walked on again, I went into survival mode, as I often did at this time of day. I was looking for a covered place under which to set up the tent. The bus shelter along this stretch of coast had been built to withstand typhoons, with four sold walls, sliding doors, and a floor spacious enough to set up a tent. But there weren't any in sight.

What I did see was a pilgrim's rest hut, built beside a small cafe. The owner came over, a small sickly-looking woman with bad hearing. I was dry for the first time in hours, and had hot coffee in hand. As we warmed up, we asked about possible places to sleep. A she was thinking, a friendly, robust man walked in; the husband, looking 20 years younger than his wife. When she asked his opinion, he quickly said, "You can sleep here," pointing at a low coffee table beside us. His wife looked horrified and began to protest. Miki and I have often commented on this sort of thing. Men, being impetuous, are often quick to offer help or things, being somewhat disconnected from the realities of daily Japanese life. The women are the ones who put the foot down. They are the ones forced into addition cooking and cleaning due to their man's whims. We've seen it most often with potential rides: the man slows down, then accelerates as the woman beside him sits shaking her head.

The man won this time. He had three friends in tow, and they invited us to join in their impromptu pot-luck sukiyaki karaoke party. It was a surreal night, of food, beer, and loads of enka. Our host thought that Miki looked like the famous Taiwanese singer, Teresa Tang, and made her sing a few of her tunes. I don't know any enka, but I made due with my usual repertoire of Okinawan classics. The woman sitting next to our host was very friendly, quite possibly his mistress. The other couple was quieter, the husband saying little besides, "More Beer!" as raised a bottle to top me up. His wife said nothing at all. All the while, our hostess stayed behind the scenes, cooking and prepping a shower for us. When she did sit down, there was obvious warmth between her and her husband, despite is possibly philandering ways.

The party broke up around nine. Miki curled up into the love seat, while I stretched my sleeping bag along the coffee table...

On the turntable: Jeff Beck, "Beck-Ola"

On the nighttable, John Nichols, "The Milagro Beanfield War"

Thursday, October 14, 2010

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

WordSmiths

This summer, my brother and I started a editing services company. In addition to our main site, New Wordsmiths, we also started a blog where we'll post flash reviews of books and short stories. My first contribution is here:

Spiritual Memoir and Eat, Pray, Love

On the turntable: Albert King, "At Montreux"

Wednesday, October 06, 2010

'Round Shikoku Day 8

After breakfast, the cook at Yuki-sō was outside our window, throwing small lobsters into a pail. Each would shriek as it made contact with the others, the whole thing a mass of writhing, spiked red. Today, the town would have their lobster market. Next month was the lobster festival. They certainly love their crustaceans.

The chef was young, with a good sense of humor. I'd joked with him that I wanted pancakes and a milkshake for breakfast. (What I got was fish and a salad.) As we set off, he gave me a hard time about the size of my pack, but then he kindly lifted it onto my shoulders.

The trail took us out past a couple of beautiful swimming beaches. We also noticed quite a few decks for picnickers that looked perfect for sleeping on, all a stones-throw from toilets and showers. Last night had been the first night since starting the henro that we'd paid for lodging, and the sight of all these free palaces pained us.

Entering Kiki, we found a sports day event in progress at the elementary school. A very old woman sat above on a hill, and gave us each a small bag of 5 yen coins as we passed. (These we eventually donated at temple 23.) We met a few other old timers down in the the town proper, all very friendly and interested in us. It's amazing how one village welcomes henro, and the next looks at them with obvious scorn.

At the far end of town, a sodden rice field was separated by the sea by a narrow concrete wall. Beyond it, the trail climbed into the hills. About half way up we found an old henro listening to the radio and smoking. On his back, he carried a sleeping bag, a vinyl sheet and a worn-out hat. He looked like he'd been doing the circuit for decades. I wonder if he was one of the guys I'd seen at the tent city yesterday.

Where the trail entered rice fields again was a pile of empty beer cans. Miki and I both felt angry. For the better part of yesterday, we'd walked past signs telling people not to dump trash along the roads. many were directed especially at walking henro. I think it is this poor behavior that is causing many zenkonyado to close, and the source of the unfriendly looks we've been getting. (In my own country, it is bums eating out of dumpsters.)

As we neared the sea again, Miki suddenly said that she wished we could finish the walk this fall, rather than keep it as an open 'someday.' We sat and talked awhile, made a couple calls to juggle our schedule, and by forgoing our Kyushu plans, scraped together an extra 20 days.

The trail climbed again, overlooking Ebisu cave and Lover's Point, before returning to sea level at Hiwasa. Many people were walking the long crescent beach, fully clothed in a way that suggested that summer was over. And the cool overcast sky concurred. Autumn in Japan means festivals, and before Hachiman Jinja, some men were putting a couple of mikoshi together. the castle stood proudly above the town on one hill, Yaku-oji on another. The temple is well known as a place to yakuyoke, and the flight of steps up to them was dotted with coins of those who looked to remove this bad luck. (Oba-chan's coins, her karma, not ours) I was 42, a bad year for males, but unfortunately didn't seemed to have the correct change. Midway up was a large urn, where a person was encouraged to pound the ash it contained in a number corresponding to your age. At the top, you were likewise supposed to strike a metal plate with a wooden mallet, again relating to how many years you've lived. On the level above the Hondo was a tall gaudy pagoda. Once inside, you'd pass through a curved dark passage, and enter a room decorated with the Buddhist hells. Then you'd climb to the top of the pagoda (heaven, get it?) to stand beside Kannon and gaze out over the town. This type of Disneyfied Buddhism can be found all over the country, and I've never been fond of it.

Near the temple was a michi-no-eki, the place we'd heard about, where the drunk henro had been rolled for all he carried. As we ate lunch in front, we chatted up a long-haired motorcycle henro we'd seen a few times. He was a Korean exchange student at Doshisha, and had done the first 30 temples in a few days. As he and Miki continued their talk, I wandered off to the foot bath and gave my poor dogs a good soak.

From here we faced a long 15km walk along a busy road. it was an uneventful upward slog to ----- Tunnel, and we rested a long while before entering its 700m length. A group of bicycle riders came up behind us, with a large support team. The leader had his hand on the back of a motorcyclist, getting an assist up this steep hill. (Settai?) Another rider was nursing a flat tire. They all had "88" on their shirts, but we never figured out what was up. Later, another guy came up the hill on a beach cruiser. No gears!

Before going through the tunnel, I put on my iPod, to block out the shriek and roar of cars as they passed through. Entering the mountainscape on the far side, John Prine was perfect. I kept him and Dylan on rotation, letting the lyrics take me from the monotony of this stretch of the walk. It was incredible how much energy the music gave me. John Prine reminded me that there are people out there who feel worse than I. Occasionally, the scenery too gave me a boost, but for the most part it was just a country road flanked by tall pines. Thankfully there were the odd cluster of homes. In one hamlet, a waterwheel thunked rice into flour. We found a trio of old women there and talked awhile. They told us that being young, we'd be in the next 'city' in an hour. While I appreciated their confidence in us, it actually took two. I also noticed quite a few public phones. These have been dying out in this age of the cellular, but in Shikoku, they are used as safety means for walkers. For the safety of American walkers in particular, there was a Pringles vending machine.

Late in the day, we entered a long open valley, with high ferocious mountains to the west. I didn't like the look of the clouds they draped over their shoulders. Closer to town, more and more buildings appeared. In front of the stone-cutter's place were a marble surfboard and Doraemon. A sign outside of Mugi announced that they were seeking Chinese brides.

But prospective husbands require a certain amount of character, and the lack of it in this town became quickly apparent. Nearly everyone we greeted completely ignored us. At the station, I asked the attendant if the inn across the street was open, and he merely said, "Why don't you call?" Prick. I wasn't keen on camping out somewhere since the town seemed so unfriendly to henro. The rain would limit us to choosing a place with a roof, and based on our welcome here, that would draw unfavorable attention. We found an inn a half hour away, then went to buy food. I was chomping at the bit, hoping to both beat the impending rain and to get away from this inhospitable place. But back outside, we found the weather had changed for the worse. And in front of us, the lights of Azuma Ryokan were now lit.

The owner was a friendly, chatty woman, especially after she started in on the shōchū. She was well-versed on the Henro, having done it six times. After our baths, we sat in the restaurant downstairs, talking with her and the inn's only guest, a young woman walking alone--the first we'd met. As we were heading upstairs, who should appear at the door but Bandage Henro-- an hour past dark. And the rain increased in volume outside...

On the turntable: Big Star, "#1 Record"

On the nighttable: Lekson, et al. "Canyon Spirits"

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Immaterial Witness

I now live in Santa Fe. This means I live amidst a hodge-podge of religions as great as at any other place or time in history. After the indigenous earth religions of the natives came the Spanish Catholicism that attempted to eradicate it. The Third Wave brought the Anglo seekers of the original draft, those artists and writers of the early decades of the last century, who created the myth of the noble Indian, which motivated further waves of Anglos to follow. More recently came the hippies and the neo-hippies, who too came looking for that simple native spirituality, yet this round of pilgrims had one eye ever on the East, diluting the local brand with elements of Buddhism and the New Age. Most recently came Indians of a different genetic strand. There are currently a handful of vedic ashrams or ayurvedic schools in the area, with yoga schools thick on the ground. Living here I am exposed daily to a wide variety of people, all grounded (or in far too many cases, ungrounded) by some belief system or other.

Spirituality in 21st Century America is far different than what I've experienced in Asia. During my own training and travels, I have noticed no real separation at all between spirituality and daily life. The evidence is everywhere, no matter the country or culture or class. Spirituality is at once sacred and personal, and is at the same time secular and universal. They walk their talk. Or more appropriately, there is little talk at all, and why would there be, since it is like talking about how to breathe or how to eat? By contrast, expressions of personal emotion here in the US feel dramatized, but that's not really our fault considering all the way we're constantly spoon fed overblown emotions by the media.

But why then, do we Americans talk so much shit about our feelings but rarely focus on what's valid, on what's real? Self-expression sounds scripted, like in a bad TV show. I naturally find myself making comparisons with the Japanese, who are as impenetrable as the concrete that they're so busy girding their nation with: a cultural and historic hardening and protecting from the inside out. By contrast, American emotions run as wild and unpredictable as a river. The approach to spirituality is interesting, frequently talked-up and emphasized as a sort of adventure. Which strikes me as odd considering that spirituality's purpose is to dam that unpredictable river of the emotions. Long ago, Trungpa Rinpoche downplayed this as spiritual materialism. In Japan, I found most people just turned up at a retreat and silently did their thing, uncomplaining about the omnipresent pain, physical or psychic. In the US, it's like it didn't happen unless we promote it. We wear our spirituality like a coat, putting it on and taking it off with every slight change in the weather. The worst are those who talk up others' spirituality, spouting aphorisms or stories of long-dead sages, as if we haven't already heard them. I often want to say to them, firmly but politely, "Just do your practice and cut the Zen talk already!"

On the turntable: Krishna Das, "Heart as Big as the World"

On the nighttable: Jack Kutz, "Mysteries and Miracles of New Mexico"

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Spurning Japanese

The grass is always greener, right?. With the coming of autumn comes the usual introspection. I'm missing Japan pretty badly at the moment. My life here, while rewarding, is far busier than I'm used to. And though difficult at times, I recognize that this return to the US is important, big-picture wise.

A few months before the move, Miki and I climbed up Daimonji. As we looked out over Kyoto, she suddenly asked, what if we didn't go? And I went cold, physically uncomfortable with the idea of staying in that city any longer.

A large part of that reaction had to do with how the local government (and I use the term loosely) presents the ancient capital. This summer, they surprised me with their capacity for shortsighted stupidity, going through with the construction of an aquarium for the 'benefit of Chinese tourists.' As I write this, the Chinese are in a rage and are canceling their travel plans by the thousands. The Heians may or may not be turning in their graves, but we can now see that the graves themselves are.

A fellow devotee to Ninkasi, Micheal has taken a sober approach in helping spearhead a movement in stopping this senseless project, one that went ahead despite overwhelming public protest. Check his Deep Kyoto for more information.

The petition site is here.

On the turntable: Neil Young, "Fork in the Road"

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Children of Water

Fall in Kyoto has much to offer. Multi-colored maple leaves strewn across stone like little lost gloves. Dango eaten beneath the full autumnal moon. Festive student carnivals played out in game and song.

This fall, there is even more. On October 1st, a band I used to play with, Morphic Jukebox, will play a short set prior to the screening of a film in which I had a hand in, "Children of Water."

It's as if I never left...

Details here at Deep Kyoto.

On the turntable: Neil Young, "Dreamin' Man 92" (I'm here too, in the audience...)

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Los Alamos

(This piece completes the triptych. Posts on Hiroshima and Nagasaki appeared earlier.)

Forgive me but the entire world was conspiring to make me think of mushrooms. On the drive in, huge clouds stacked up with weather above the mountains, including a tall mushroom shaped-cloud rising from the Jemez. After tracing a line rising diagonally long the edge of the Pajarito plateau, we arrived in Los Alamos, and immediately sought out lunch. The Hill Diner is an old favorite, though not quite as old as the décor would have you believe. It speaks of woodsy roadside diner, the paneling hung with photos from a half-century gone, with old neon beer signs, and garage sale items like skis and snowshoes hanging from the walls. Mushrooms showed up again here, batter-fried and flanking my chicken fried steak. This place is popular with both the locals and those working at the labs. The ‘good ole’ lost America’ theme attempts to whitewash some of the threat that hung in perpetuity over those ‘gentler times,’ a threat birthed less than a mile away. In a conspiracy of irony that only the universe can craft, I noted Asians at about a third of the tables here this Saturday morning.

After lunch, Miki and I wandered around town, a pleasant place like a small New England college town, trees shading dormitory-style housing for the lab families constantly revolving in and out of their temporary assignments at the Labs. It would be a pleasant place to live but for the work going on across the canyon. We stopped off in the tourist info center to see what this town had to offer. I desperately wanted to find something attesting to the local character, to draw my attention away from the obvious. As a fan of history, I find that I visit places with a fair amount of projection, scanning the landscape and residents in an effort to find connections with those events that brought them onto the world stage. I’ve done it in Vietnam and Cambodia, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, using tragedy as an information sieve, until time and the locals present me with a different face that allows me to let go my stereotyping. Then I can finally accept the place on its own terms. I’d done it earlier in the day with the cloud formation, and in coming upon the ruins of an elementary school in mid-demolition. This latter caused me to exaggerate the presence of tragedy here, but what else could I think, being presented with such an obvious example of the decline in education spending in the town which, again, started the arms race and the current blank check approach to military spending?

Scanning the walls of the tourist center, I so badly wanted to find mention of an ancient Native American festival, or a photo of a ruined Spanish church, or read a about some Anglo bigwig who’d established a modest ranch which eventually grew into this town. But all I could find were T-shirts and coffee mugs tastelessly emblazoned with pictures of an exploding bomb, hung above bags of “Atomic chili pepper.’ A sign on the glass door listed events held during the summer in this, “The Atomic City,” including a concert being held, without any apparent irony, next Friday, August 6. The view beyond the poster and through the glass door revealed a town whose history began with the atomic age, and seems stuck there, both in architecture and in mindset.

A short walk took us to a series of lovely buildings that look as if they belong in an Alpine town. Had I visited them prior to November 1942, I’d have found that history I’d been searching for, in the form of the Los Alamos Ranch School, whose alumni include the CEOs of a few major corporations, as well as William S. Burroughs and Gore Vidal, though these two latter names inevitably escape mention. On an autumn day less than a year after the US entered the Second World War, the grounds were bought by the military for a top secret project. Some of the buildings are now being used as the Los Alamos Museum. The actual place where the bomb had been designed is now a large open space with a pond in the center. It was here that we’d meet up with Pax Christi for the peace march. Along the way, I stepped over a patch of mushrooms, barely noticeable amidst the neatly clipped grass.

The peace march was to begin at Ashley Pond, site of where the first atomic bombs were built. There was a picnic going on, children running after balloons, and the adult members of the local YMCA queuing up to buy BBQ from a red trailer with a flaming pig emblazoned on one side. The Pax Christi people weren’t far away, their banners with anti-nuke slogans spread across the grass. In a pile was a collection of burlap sacks and dozens of small bags of ash that we were expected to drape and decorate ourselves with for the march. This was inspired by the biblical story of Ninevah. When threatened with Divine destruction, the inhabitants of the city repented, putting on sacks and smearing themselves with ash. Sacks were traditionally seen as a sign of deep repentance and humility. Ashes were often included as a further symbol of personal abhorrence and chagrin.

The organizer of this march, Jesuit priest John Dear, was being interview by a TV station from Albuquerque. We’d met John months ago when he gave a rousing talk on Gandhian non-violence at Upaya Zen Center. He’d really motivated us there in Santa Fe that day, so it was very disappointing that the only attendees who’d actually turned up for this event were Miki and myself. Prior to setting out John led us in prayer, where, he neither accused those involved in the making of nuclear arms of being evil, nor asked God to forgive them. (In keeping with the Ninevah biblical story, where God states He is showing pity for the population who are ignorant of the difference between right and wrong ("who cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand"). Instead John simply asked us to repent our own complicity in violence, and to beg the god of peace for a world free of nuclear weapons.

Then we marched, moving down Trinity Drive, crossing with the light at Oppenheimer. Through breaks in the buildings lining the road, we could get glimpses of the Labs standing with a certain majesty through the trees. They’d been built in the 50s, when the one-off Manhattan Project had spawned a child that had grown with the arms race. Along the way, a couple of people stopped to collect apricots that had fallen from a tree. One woman nearby nodded her head toward the labs and said bluntly, “You sure you want to eat those?” The apricot collectors quickly dropped the uneaten fruit back onto the grass.

We stopped our march at the hospital that sits beside the bridge leading over the canyon to the Lab’s front gate. About fifty young people showed up about then, all carrying sunflowers. This was “Think Outside the Bomb,” a national youth-led nuclear abolition network. They were here to protest Obama’s policies regarding nuclear strategy. While professing in public a reduction in nukes, the administration was instead going forward with policies set up by their predecessors, yet their proposed increase in the amount of plutonium pits to be constructed at Los Alamos would go far beyond what the Bushies had envisioned. The group was camped out in the hills near the Sanctuario de Chimayo for a week of workshops on permaculture and on non-violent protest. They’d be back on the actual anniversary of the bombing on the 6th, for a protest up at the Labs themselves. (And at which eight of them would end up arrested.) For today they’d settle for a less confrontational demonstration, for we’d go no further than Omega Bridge, and would do little more than sit and meditate.

John gave the word and we all sat down on the sidewalk. While some had smeared their faces with ash, other had simply outlined their bodies. A couple of people had emptied their bags in a clump, tracing with their fingers small pictures or simply the number 140,000, the believed number of nuclear bombing victims. We stayed like this for half an hour, quietly reflecting. A light rain began to fall, and I was reminded of the black rain that had poisoned so many in Hiroshima. Then, after the final signal, we all got up and began walking back to the park. As on the march down, we were exposed to a variety of reactions by the locals. Some flashed peace signs as they drove by, or honked their horns in apparent solidarity. Others yelled out in opposition, words mostly lost in the wind but for the swearing. It was predictable how the reaction of the driver consistently matched the type of vehicle driven. Most memorable was the extended, black-gloved middle finger of a Harley rider.

Back in the park, John gave a closing prayer then introduced a few speakers. One of them was Col. Ann Wright, famous for her resignation from the military when Bush okayed the invasion of Iraq. Most recently, she’d been on the Gaza flotilla that had been attacked by Israel last June. At one point, Ann asked us where we’d all travelled from, and when Miki yelled out “Hiroshima!” my wife suddenly found herself before the mike, giving a brief speech. A couple of folk singers then began to gather the crowd together in a sing-along, but Miki and I quietly slipped away. We did a symbolic circumabulation of Ashley Pond. Two black cranes extended out of the water, their iron material an ironic contrast to the delicate paper cranes of the peace park of Hiroshima.

A few hours later we met again down in Santa Fe, in the wrap-around bar of El Canon, with its million-dollar view down San Francisco street, toward St. Francis Cathedral lit gold by the setting sun. We found ourselves with John Dear and other organizers of the event, in a sort of debriefing. They seemed disappointed at the numbers, a mere hundred when last year they’d had three times as many. They also mentioned that this year’s march had seen the most vehement reactions they’d yet seen. As Miki and I headed toward home in the heavy storm, the group was questioning the event’s significance. According to the local news team that had been there, very little, as they gave us less than 10 seconds coverage, giving no mention of who we were or what our message was. To the average viewer, we’d appear to be just another bunch of loony hippies.

But really, what did they think? I know quite a few couples that live up there, most of whom work at the labs. When I mentioned that I’d been at the march, one woman seemed supportive, mentioning that her husband had been quite active in disarmament work. To which he gave the hilarious quip, “Yeah, disarming the Russians.”

Waning a bit more perspective, Miki and I returned to Los Alamos a few weeks later on a quiet Friday afternoon. We wanted to visit the museums and see how they presented ‘their side.’ The Historical Museum is, as mentioned earlier, in one of the old cabins that once made up the Ranch School. I’d entered with a certain amount of cynicism, but as I made my way through the quaint narrow rooms, I was quite taken with it. Represented was the scientists’ story, composed of the somewhat comedic tales of the civilians who found themselves sudden residents of a town that literally appeared overnight, one that remained in complete secrecy for over two years. I spoke with the curator for a while, telling her how pleased I was to find this place so free of propaganda. Through the words of Oppenheimer and others, I could really see that the scientists were the only ones who saw the real scale of what was going on. They thought that their work in presenting mankind with its complete elimination would introduce a period of enlightenment that would end war altogether. She told me that the scientists themselves had felt so betrayed by the subsequent Cold War behavior of the military and the government.

Their tale is better told across town at the Bradbury Museum. The POV here is pure propaganda, attempting to whitewash history in order to make nukes palatable. In the film, “The Town that Never Was,” there was a line about the local natives who were “happy to give away visiting right to their ancient ancestral grounds, for the good of the nation, “ that was particularly disgusting. The cold, scientific approach to information here was predictable. As was the sight of the US Government plates on the vehicles out front.

It was a beautiful day on the cusp of autumn, so Miki and I chose to drive home through some of those same ancestral lands, through the canyons that flank Bandelier. I asked her about her reaction to the day and the town. She said that she didn’t harbor any bad feelings toward the US. In the war, both the US and Japan were equally victims and aggressors. The past is done, and it is more important to focus on the future. No one wants nuclear war, so we should all work together to prevent something like this from ever happening again.

I looked out at the soil that was so sacred to the natives and wondered if they too have such a magnanimous attitude.

On the turntable: Ry Cooder, "River Rescue"

Tuesday, September 07, 2010

'Round Shikoku Day 3

I awoke sometime before six and went outside to sit and look east to where the sun was pulling itself over the pull-up bar that is the horizon. It had been a long night, a siege against cockroaches and mosquitoes. I sat in the peace of morning, the sky a clash of blue and gray that foretold rain. 50CC Henro came out and as the first act of the day, lit one up. A severe bout of coughing followed, guaranteed to awaken anyone still sleeping in the huts behind him. Yep, that first one always tastes best. Judging on last night's performance, he'll go through a dozen more before setting off on his little scooter. He was a good guy, good-natured but for the perpetual butt in his mouth and his little transistor radio, constantly switched on. This latter habit, in conjunction with the high back rest he'd welded on his bike, reminded me of 'Quadrophenia.' A Real Who-nro.

His roommate was a soft-spoken young guy who was doing the 88 Temple in reverse order by bicycle. We all separated at 7am, by our various modes of transportation. It was a half hour on foot to Temple 11. This beautiful little zen temple was tucked away in the corner of the valley, just below where the trail leads up toward Temple Twelve. It had the quiet, forlorn feel that Miki and I love so much, until a group of car pilgrims came and chose to destroy the quiet with a noisy argument about nokyo, as usual. The priest on the other side of the counter wasn't much better, processing us all with a curt, "Next! Next!" Despite this, his calligraphy was the most beautiful so far.

The trail started steep and got worse. The first section was lined with Jizo, whose form repeated nearly ceaselessly for the next five and a half hours. Apparently many people didn't survive this stretch. Approaching the top of the the first crest, I spotted a young Henro sitting and admiring the scenery. I held up my hand in greeting but didn't speak to him since he was wearing what I thought were earbuds. It dawned on me an hour later that he was deaf. The view from this height was of the valley we'd spent the last two days traversing, now covered by a layer of mist due to the coolness of the air and from the smoke of burning rice husks rising from a dozen farms. The smoke hid the view of the highway, and some of the bigger buildings, creating a view that was almost softly Himalayan.

We spent most of the day on this trail, making our way toward Twelve, along a path that wound up and down as if testing our resolve. Besides the ever-present Jizo, there were also plenty of small signs tied to the branches of trees that offered pithy expressions as a means of urging us on. Like Burma Shave ads for the Buddhistic set. A few small temple halls showed up here and there, eroding slowly into forest. We broke for lunch at one of these, and were soon joined by Shibui Henro, dressed in the full kit. He was an interesting guy, doing the full 88, joined by his father for this first Awa section. I hope we run into him again.

The day took us over three passes, each of them a challenge. After the second tough ascent, the pilgrim turns a corner to see the large figure of Taishi atop a flight of stairs. Very encouraging. From here we dropped and dropped and dropped into the valley, past farms with their stone walls and steps, also looking very Himalayan. The valleys in Shikoku have long held secrets of people looking not to be found. Their villages cling to the hillsides, rarely containing more than a dozen homes.

The trail bottomed out at the base of this valley, where a stream was rushing between boulders. Above it was a sign saying that the next climb was the steepest on the entire pilgrimage, and would take 50 minutes. A woman of around 70 hobbled up then, supported by a pair of walking staffs. When she saw the sign, she literally plopped down in frustration, announcing loudly that she'd eat lunch. She began to talk with us, but after a couple of minutes, began to get strangely aggressive, then abruptly walked off, saying she'd eat lunch elsewhere. We found her awhile later, squatting and eating onigiri in the middle of the trail.

The final ascent was as tough as advertised. My heavy bag and I rested three times along the way. Once, I heard the jingle of a bell and clack of a staff and assumed a henro was on the trail just above me. Reaching the next clearing, I saw merely a lone Jizo on an altar, with a bell above him and a staff at his feet. There was no one else around. It was strange, but then again, I'd already hallucinated three times already today. This happens to me sometimes when I'm fatigued, and the straps of my pack are pressing into the optic nerves in my shoulders. One thing I didn't imagine were all the vipers I saw on the climb, including one that darted across the trail right in front of me, in pursuit of lunch.

We finally reached the temple. Even with our bags, we were two hours quicker than average. I was really feeling this weight for the past two days, but seemed to have found my groove. Walking the final set of stairs, a guy began chatting up Miki, and I heard him complaining to her about how curvy the road had been, the drive taking over an hour. Jesus.

Sitting beside the gate was a woman from Flagstaff. Now living in Himeji, she was doing the Henro after having previously done pilgrimages in Italy and Spain. We also saw the two henro who'd been our comrades in yesterday's parade. We did our rounds, then went up the last 30 minutes to Okuno-in. Not many walk this trail and it showed. It was dark and wildly overgrown, with narrow sections leading over high drops, and large swaths taken out by landslides. Mountain sacred to the Yamabushi always have the same look as this one. A place where dimensions overlap. Halfway up is a large rock face where Taishi beat the giant snake. On the peak itself is a large altar. We sat behind it and drank in the view of the peaks before us. We were at 938m, but these were much higher, including Tsurugi which dwarfed them all. In nearly every valley was a small cluster of homes hanging to the steep mountain faces. They were humbled by the large slabs of rock on their slopes. I had never realized that Shikoku was this wild.

Back again at the temple, we grabbed our gear and moved slowly off the mountain. Miki was using a staff now for the first time, a thick cherry branch that she'd found up at Okuno-in. Despite our quick speed of the morning, we'd lingered through most of the afternoon, and hoped to get down to a rumored campsite before dark. If it was full, we'd have a long, dark walk before meeting road again. Entering a village, a man offered us four mikan. At the far end of his village was Joshin-an, where Emon finally caught up to Taishi. His staff had grown into a tree of unbelievable height. Beyond it, we dropped into an orchard, then down into a small village beside a small river. It was a peaceful place, maybe eight houses, three of them empty. There was also an elementary school. We asked at the lone village store if we could camp there, and the young woman working there told us that we were welcome to sleep across the road at a small covered space that they sometime use for their market. This woman had herself been a henro, but had liked this valley so much that she'd stayed on to help out at the store. Twenty-two, she'd given up on life in the city and is looking for a life of farming. When we first saw her, she was cutting the stems off fresh mikan while listening to sumo on the radio. She offered us sweet potatoes and barley tea as settai, which we enjoyed as much as the conversation.

We eventually set up camp, then went to eat at a pilgrim's rest hut that we'd noticed on our way into the village. It had electricity, allowing us to read and write in our journals. Yet after about an hour, an old man came up out of the dark and grumpily told us that the hut was only for daytime us. Go to bed! At 7:30. It definitely diminished the warmth here. If you make a hospitality area beside your house, and show no hospitality, what was your motivation in the first place?

On the turntable: Supertramp, "Retrospectacle"

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

New Bottles

This return to the US has me staring down the barrel of the gun of aging. In Japan, no one could peg just how old I was, often guessing a decade younger. Here, I am expected to act my age. In Japan, I could constantly reinvent myself, the judgments and perceptions of the locals going no further than my identity as gaijin. Beyond that I had all the room in the world to be who I wanted to be. Now I'm back in my own cultural context, and can't escape the framework.

Yet how AM I defined here? I find myself as Neither/Nor. I'm a native New Mexican who no longer recognizes his state. I'm as much a gaijin here as I was in Japan.

I'm most puzzled how do I fit into all of this as an American. Since the national nervous breakdown year of 2001, I no longer know what that means. The America I see in the 21st Century is not the place I learned about in school (however fictitious that was). I don't remember such a high degree of fear and anger, of distrust and ingratitude. While most of the Japanese I knew tried to harmonize and blend with what was happening around them (manifested at its worst as the dreaded 'shoganai'), Americans try to dominate the space. I see it in the conversations, in the body language, in the government policy. I don't really want to be part of it.

While in Japan, I'd made a conscious attempt to be a big fish, as a yoga teacher , a writer, a musician, a martial artist. It was exhausting. Here I want a quiet and simple life. To do my job and go home. But those around me (God bless 'em) are pushing me to both succeed and exceed. Such an American thing, to fill up and overflow the container that is your life.

On the turntable: Yes, "Tales from Topographic Oceans"

On the nighttable: Stanley Crawford, "The River in Winter"

Friday, August 20, 2010

Over the Line

A decade in Japan created in me the habit of wearing shoes without laces, preferring the whole Mr. Miyagi, slip on-slip off thing. The shame about this is that I lost a creative outlet of artistic self-expression: tying a pair of worn-out shoes together by the laces and throwing them over a power line.

On the turntable: Ricardo Lemvo, "Ay Valeria!"

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Izu Dancing

My work situation has finally stopped thrashing about, entitling me to some free evenings. The nightly monsoons have kept me away from the live music down on The Plaza, so films once again present themselves as alternative. After the marathon stretch of Kobayashi's "The Human Condition" (we could only handle one hour doses of this brutal, 10 hour masterpiece), we've settled in with Shimizu Hiroshi. He reminds us some of our beloved Ozu, manipulating actors as props as a means of diminishing the subjectivity of role, and creating a story that speaks to the universal in us all. If Ozu was a maker of tofu (as he famously claimed), then Shimizu is a master of okayū. He shares Ozu's slow pace of storytelling, yet utilizes camera techniques seemingly cribbed from European Surrealist films of a decade earlier. These effects weren't commonly seen in Hollywood until being 'pioneered' in Citizen Kane in 1941.

Shimizu was one of the first directors to commonly use location rather than sets. To view the dirt roads of 1930's rural Japan is to see the contemporary Laos roads over which I traveled this winter. It also shares a lot with the deep-country Shikoku pilgrimage trails I walked last autumn, minus the power lines and vending machines. Shot on a bus actually traversing the Izu countryside, "ありがとうさん” ("Mr. Thank You") features scenes of a long gone country life rolling behind the characters , showing it such deference that the landscape itself eventually becomes more important than the actors themselves. It is one of the earliest road movies that I can think of. As I watched it, I surprised myself in that the film reminded me somewhat of John Ford's 'Stagecoach' (filmed three years later), where archetypes are thrown together, then bound by the landscape through which they pass. But rather than solidifying that bond through the drama of an Indian attack, Shimizu's film stays true to the fact that most of our human encounters stay light and impersonal, in our sharing moments with strangers who will remain just that. His films offer glimpses of life that, while possibly thought mundane at the time of release, bask in a beauty that is both bittersweet and enchanting, made more so by their fleeting nature.

On the turntable: Drive-by Truckers, "The Big To-Do"

On the nighttable: Hammett, et al., "The Essence of Santa Fe"

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

'Round Shikoku Day 2

I'm in the process of transferring my Shikoku journals to digital, though I hope to see the final result revert back to a piece of analog technology, bound in cardboard. In the meantime, I will post occasional tidbits, about once a week, as the yoga teacher in me pounds and twist the words into proper alignment.

(As always, more recent lifestuff over at Bentos...)

The stars over Tokushima have proven to shine bright and clear. Under them I sleep better than expected, considering I'm sleeping in a small three mat room with two others. The late arriving pilgrim, a 20 year old student from Toyama, was on the couch, his legs extended up the wall, poor guy.

I get up at 6:30 and have my breakfast out in the sun. The owner of this 'office' where we slept pulls up on his fancy Italian bicycle. Like last night, he had a small watermelon in one hand, a knife in the other. I suppose I've been reading too many tales about the Taishi, because ordinary people are beginning to take on fantastic properties. It all feels like the Wizard of Oz somewhat. I dub the owner 'The Watermelon-Bearing Boddhisattva.'

It takes an hour to get to Temple 6. We pass many jizo, their faces lit by sunlight. I figure that most have been standing here long before any of these houses were. Along the way, we three pick up another walker, who'd been resting in a bus shelter. We eventually spread out along the roadside, a proper henro parade. I'm in the lead, humping my huge pack like that guy in any Vietnam War film, the one who totes the heavy M60, and who, when the firefight breaks out, merely shifts his weight to his back leg, bellowing, as the shells cartwheel around him in slo-mo. Why am I the one on point anyway, when I'm the only one who can't even read the signs well? Probably at the exact moment as I was having this thought, I accidentally stray from the walkers' trail and follow instead the one meant for cars. But I'm too busy singing Blues songs in time to the rhythm of my feet. I make up a new pilgrimage precept: Don't Play Air Guitar on the Pilgrim's Walking Staff.

We do our thing at Temple 6, then Miki and I decide to leave the others behind for the short walk over to Temple 7. We find a Kumano Shrine here, the passage between the gate and the kami being a long narrow corridor. A Hong Kong couple at Temple 7 laugh as I approach, and I later realize that I'm wearing my Bruce Lee T-shirt under my pilgrim robe.

It's another hour before we reach Temple 8. We had stopped midway for a break, gnawing on a day old sweet potato beneath the freeway. Temple Eight stands at the end of a valley, and we hear it before we ever see it. We've dropped our bags behind some stone jizo at the base of the hill, since we once again need to pass by here on our way to Temple 9. As we admire the Benten Shrine on the pond, we hear a beautiful voice chanting near the pagoda. We are saddened to find that it is a mere recording. Up at the Taishi Hall, I find an old man with the outfit of a seasoned henro, chanting powerfully and devoutly. When he finished, he seemed taken with us, offering seasoned advice and kind words. Miki had been suffering quite badly today, and he was talking about how you have to shoulder your burden and do the best you can, asking Taishi's help if needed. He was yet another character in our growing tale, the sage who shows up to deliver the exact wisdom we need at the time. I find that a trend in these people is a growing devotion to Taishi. This is considered a pilgrimage of personality, yet to follow such a person is in itself an act of great faith. When we leave our own aged sage, I notice that he is wearing a sash written with Dai Sendachi. He then gives us his fuda, the red color of one who has done the pilgrimage 50 times or more. I'm smirking and thinking of soccer, but Miki is beaming like she's clutching one of Willy Wonka's gold tickets. She tells me it is incredibly auspicious to get one at all, and we've been out here for less than 24 hours.

It is another long walk to Temple 9. The houses drop away and the fields lengthen toward a grove of tell-tale trees. Across from the main gate is a small shop selling udon noodles. Its two seats are occupied, but we are led to a bench out front. I'm happy here, feeling like an extra in a period film. We eat tarai udon, which is firm and tasty, preceded by sweet potato as settai. As we eat we encounter the smiling Dai Sendachi again, his demeanor changed from sage to grandfather, as he walks in the main gate with a couple two generations younger. We also see the two guys from our parade this morning. There are quite a few people coming and going, this still being the long Silver week of holiday. After our meal, we finally enter the temple. There is a rare Japanese reclining Buddha here, but it isn't on display today. I want to use the restroom, but the only one I see is for the handicapped. I find it locked. After waiting at least 5 minutes, I try the door again, and again, then finally ask the woman at the nokyo-jo if it is purposely locked. She says yes and asks me if I want to use it. Of course I do, and why did you choose to ignore my rattling of the door as you are sitting a mere five feet away? And why would you lock it in the first place, making it laborious for the handicapped to use at all? Is this beautifully built chamber built for their benefit, or for yours?

My mind is growing sour. All of these temples look too built up and modern, funded by our offerings as pilgrims. Entering a nokyo-jo is like entering a comfy, air-conditioned office, our paperwork deftly processed before we are whisked away. It has the feel of a stamp rally, and I'm not getting much of a spiritual vibe at all due to all the concrete, electric doors, fully automated toilets, etc. When we do feel like lingering, the crowds elbow one another, sending us screaming outside to the path once again. This is where I'm beginning to feel that spirit lies, personified in last night's caretaker, in the Watermelon Bearer, in the Dai Sendachi, and in whoever owned the shop that left some sugary sweets and barley tea out front, for us to enjoy during the long walk to temple 10 on a day growing hot.

But arriving there presented new challenges. We still hadn't seen any buses yet today, but the number of cars created the identical result, with the van drivers aggressively honking, and the drivers of the two luxury cars who had the audacity to park directly in front of the main gate. I found myself trying very hard to find acceptance at anything that arose on the pilgrimage, but I was continually amazed at what people accept as acceptable.

The 333 rough stone steps were enough to humble anyone, but the crowd here was still too big, too pushy. For the first time, we had to queue at the nokyo-jo, processed like an assembly line. These mountain temples are where we usually find the most spirit, but the numbers here stamped it out. On the way back down, I told Miki that we might find more spirit if we forego the material nokyo collecting in order to make it more pure. She asked, "Do you really want to?" I laughed as I said no.

We'd left our bags at a shop at the bottom of the hill, where we sat out back and ate ice cream. This five minute break set up a chain reaction. Thirty minutes later, as we waited for a stoplight to change, a couple waiting at the same intersection offered us a lift. Surprisingly, it was an independent taxi, which confused us a little. As the ride was offered as settai, we accepted, having agreed before the trip not to actively hitch, but to take those rides freely offered. The couple was from Sakai, and did a section of the pilgrimage each month. Today, they had started their second go-round. Another mythical figure, The Taxi Henro.

Having saved us a 7 kilometer walk, they dropped us at Kamo-no-yu Onsen, which offered free huts for walkers. I relished the bath after a couple of hot days. It was late afternoon on a holiday, so the baths were busy, mostly with rough-looking laborer types. At one point the rotemburo was filled tough men talking tough, like I'd stumbled onto a yakuza meet. After the bath, I climbed into a massage chair. It was a high tech modern type, which did everything but knead my shoulders as I'd so desperately hoped.

The onsen also had free bicycles, which we rode up to town in order to buy food for the long stretch of mountainous section tomorrow. It was a delight to ride bikes for the first time in weeks, our legs having their own holiday in tracing a pattern not used for walking. Our stomachs too had a treat in a long meal at Joyful, me downing beer and pasta in a pathetic attempt at carbo loading. Stuffed and happy, we made our way back to our shabby two-mat shack, perfect for the pair of us.

On the turntable: "Harry Nilsson, "The Point"

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Slouching toward Shikoku

9/19/09

...we awake at 5:30 and walk toward Oku-no-in as temple bells begin to peal. The cemetery looks almost two dimensional in the fog. Three monks are chanting at the Gōkyo, slower and deeper and even more Tibetan than at the service yesterday. We go around to back to Taishi's tomb and meditate awhile. Then a quick prayer asking for protection as we're about to trace his footsteps across Shikoku. On the walk back, sunlight begins to spot some of the mossy stones, animating them.

We have breakfast, pack, then get a bus for the cable car down. We are standing in front, the car submitting to gravity, moving down the steep pitch as if an automobile in idle. The driver has little to do but brake and inch us into the station.

On the next train, we lurch through the mountains toward the River Ki. We are once again back in the wild land of the gods, and I can see how this formidable range kept out invaders. Back on the plains, today's invaders are the other passengers. I hate that we have to pass north of the Ki and out of the land of the dead, then return all the way back to Osaka. I'm not ready for city yet. The bodies hem in much too close, and I can't quite concentrate on my book, having been too relaxed by all the space I got these three weeks on the road and in the mountains.

Then on the ferry. I spend most of the crossing filling in my journal, but feeling the need for perspective, I go out on deck. If I go from dry land to dry land without a glimpse of water, I'll never be sure I actually left Honshu. It is windy, the waves high, large freighters rolling as they pass through our wake. Tall shafts of white reach up Awaji's rocky southern sides. I cross to port and look past the bow at the shoreline of Shikoku which we'll walk for the next few weeks or so. I go back inside to pee, my stream drawing a crescent moon as the boat breaks the swells.

On the turntable: Fleetwood Mac, "Roadhouse Chalk Farm"

On the nighttable: Frederick Barthelme, "The Brothers"

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Sleeping with the Taishi

09/19/09

Tentokuji is a large temple that sprawls around its garden. We seem to be the only independent travelers here, so besides our own room, we get the adjoining room for our meals, plus we get the baths to ourselves. If it weren't for the morning chants, I'd feel we were in a nice ryokan. We are awakened by the sound of bells resonating across the hour preceding dawn. At 6:30, we kneel before the altar in the Hondo, listening to the priest and his son chant in low guttural tones. With the low light and the clang of cymbals, we could be in a Tibetan monastery somewhere deep in the Himalaya.

After a sparse breakfast, we move toward the Gorin, we that we have this too to ourselves. The silence is suddenly cut by leafblowers. As I've learned in Kyoto, this is apparently a new traditional practice with modern monks. I really miss the soft shush-shush of a bamboo broom moving over stone. The sunlight on the buildings is enough to impress; our photos naturally framed by more of those massive cedars. The world surrounding the dull wood is particularly green this morning. We enter the Daitō first, which I decide later is the most impressive. This open pagoda is the womb mandala, with the Sun Buddha at its center, flanked by four other Nyorai. All towering gold, they stare toward the south with calm impassive expressions that somehow change perspective with every footstep. All these in turn are flanked by large well-painted pillars of 16 Boddhisattvas, each distinct and lovely.

The Kondō is next. A common theme between the structures up on Kōya seems to be those towering ladders stretching up to the roofs, and the paper cutouts before the altars.

The figures here in the Kondō look more Indian than in the other halls, including one Shakyamuni who looks remarkably like Jesus. Back clockwise around to the front again, the incense sticks that we lit earlier send trails toward the high wooden beams.

We pass the morning walking to all the other old structures on the mountain. The odd grooves in the wood trick my eyes into seeing sanskrit characters. Approaching the Saitō, I am facing a sight familiar from the cover of the book I've been reading. Walking the veranda of the low squat Miedō next, I am serenaded suddenly by that Can-Can music from the French Follies. The sports festival from the adjoining high school is using it as their opening procession, a song better known as BGM for lowbrow sex shows. I love (and sometimes loathe) Japan for its lack of context. I usually counter this with my own sense of irony, which deepens as I stroll a 1200 year old building with this song filling the air around me.

Tourists begin to come now, in groups of twos and threes, all of them foreign. Most of the Japanese come on bus tours, though they're nowhere to be seen. The single Japanese travelers seem to be henro, tanned and thin, clutching their staffs. A smaller version of the latter is being tossed onto the flames over at Aizenmyo. A monk sits before the goma pit, alternating throwing more tablets on the flames, tapping the metal hibachi with his 'tongs,' and moving his mouth which intones syllables we can't hear.

We head west out of town, which, while not as lovely as the eastern section, has the same appealing ski town look of two-story structures, the view of the towering cedars unimpeded by power lines. Add the fact that this is all surrounded by 117 temples allows the beauty to expand exponentially. At the town's far end is a massive Daimon gate, opening onto an array of trails leading away from the peace the prevails up here on this plateau. By contrast, Kumano had been so rugged and untamed, the lair of gods both loving and wrathful. Kōya is pure Pure Land.

We walk down the street past a pair of ancient women who wave to me. Miki is in turn greeted by a foreign woman on a bike. We stop at the museum, modeled after Byōdo-in in Uji. Inside we find the rooms to be high and wide and oddly Victorian. There is plenty of statuary to admire, including one series done where each of the wooden figures has eyes that are alive, skin that begs for a caress. While I'm not often taken with written scrolls, here I'm most amazed by a sutra done in microscopic woodcuts, and a Heart Sutra done in blue.

There's not much English, so I head outside to wait for Miki, reading while a persistent bee practices landings with my foot as a runway. Then it's lunchtime, a lovely moussaka back at International Cafe. The owner is in conversation with an older priest relaxing in his samue with a cuppa. Besides the foreign tourists, this place seems popular with the local monastic set. A young nun comes in, looking exhausted , but with a grin that is the smile of any young woman in her 20s with a piece of cake before her. A foreign monk also comes to the counter, probably the Swiss monk who I've heard has lived on Kōya for 8 years. We too get our chance to chat, and after mentioning our impending plan, are given an 'underground' list of lodging for the Shikoku pilgrimage. He tells us that he doesn't give it to just anyone, making me suddenly feel like a character in "The Beach." He then knocks 400 yen off our lunch. Our first settai.

We work our way toward Oku-no-in, finally. On the way, we pass through the Burmese temple that has a tie with the book/film, "Harp of Burma." We make another stop at Karukayadō, with its story of Karukaya Doshin and Ishidomaru, done in murals. Then we cross the first bridge.

It is an incredibly serene world here. the height of the cedars comforts, as does the softness of the moss. They too are the Diamond and the Womb. The proud and ancient figures of the Gorintō are the sentinels who grant us leave to pass. Jizo dot the forest as if in a game of hide and seek. The graves are like an all-star team of Japan's greatest historic figures; they who made the country great. Not just the number, but the variety of people represented here further emphasizes Kōya's greatness. This mountain has quickly become my favorite place in the country.

After passing a couple hours looking at graves, we finally come to the Mizumuke Jizo. Here we get our first nokyo stamp for the henro. Next we'll get a tōba for Ken. I can't remember the exact kanji for his kaimyō, but the woman at the window tries writing out my pronunciation on a scrap of paper first and I immediately recognize them. The next task is to choose before which of the figures to place it. Of the seven standing beside the small stream, I pick the smallest, the oddest shaped, one slightly ugly. It should be easy to find in the future. I apply water to the strip, the damp ink streaking downward somewhat. We then cross the final bridge.

To the right of the stream stand a series of moss covered mounds dedicated to the Emperors past. Before us is a large hall dark but for the hundreds of lanterns. Each goes for $25,000. Despite the price, they also line a tunnel like path one floor below, plus another two-level hall next door, built especially for the overflow. We move around to the rear of the hall where a tour group is wrapping up their chanting. They move on and we're alone with Kōbō Daishi. We pray, then sit and wait for dark. It is completely silent, no other tourists in sight. The silence continues into dusk, then a lone cry comes from the forest, a reminder that night is the animal world. The subsequent calls of birds and insects has a different quality than in the day. Satisfied that night has come, Miki and I turn back to begin our 2km return through the cemetery. The path is lit by soft overhead lights, but they're spaced about 100m apart, forcing you to walk in darkness cut only by the low light emitting from some of the toro. This helps to created some fantastic shadows. The huge gorintō silhouetted against the night, looking like one of Sendak's Wild Things. Faces of statues also come out of the dark, the trees now become beams holding up sky. One of the most magical moments of my life. On the path, we pass only a few others, all foreign. Miki remarks that most Japanese wouldn't do this, being far too busy with baths and dinner. Ours too awaits, as we hurry against the cold...

On the turntable: Beirut, "Gulag Orkestar"

Tuesday, July 06, 2010

To the High Wild Mountains

We get on a train before seven and spend the morning revisiting the songlines we'd made over the past two weeks. It was like watching a slide show at high speed. We have the "View Car" to ourselves. For some reason, no one else chooses to sit in this wide open, spacious car with glass running from floor to ceiling. It's a long journey, one that won't get us to Koya until early afternoon. The final approach on a cable car inches us up a slope at nearly 45 degrees.

We spend the afternoon walking the temples on this quiet mountain. We follow a saffron monk with billowy sleeves to Nyonindō, where until 100 years ago women would have had to finish their ascent of this sacred mountain. It stands just outside the town's gate, so seems a good place to begin our rambling. Inside the temple hall is a statue of En-no-Gyoja, with fierce glowing eyes that bring life to the darkness. In front of neighboring Benten is an ihai for the comfort women of WWII. The main priest here answers all our questions, his effeminate nature perfect for his position. Like the Hijira of India, or the transgender shaman of many cultures, I wonder if this role is chosen by the community.

We make another stop next door at Naninji, with its picture of Namikiri Fudo, cutting through tempestuous seas so that dharma-laden Kukai could return home safely from his studies in China. A well behaved dog sleeps on the 'front porch.' I toss pebbles to a kitten, which chases them around spasmodically as they bounce. Behind the hall is a circular pool ringed by at least a dozen Jizo. It looks remarkably like a rotemburo. A small mausoleum to the Tokugawa is just over the wall, like a mini Toshogu, yet unlike the busy bigger shrine, this one stands quietly among the trees. The trees on Koya deserve special mention, huge and majestic and old. Japanese forests are at their most beautiful when left alone. One of the smaller groves hides a small temple that looks to be one of the oldest in town, and the Thai script over the main gate hints at international connections.

Beyond it, the Kongobuji too is nearly hidden, the forest thick around this simply massive structure. There are huge buckets on the roof, with long ladders extending toward them. We take our time wandering the rooms and long corridors, many lit with oil lamps from centuries ago. We take tea in a large hall, which contains a painting of the character of "Shin," stylized to look like a mustacheo'd figure with a doughnut. A nun walks past the hall and down the corridor. Walking behind her, I note how she has retained her femininity despite the shaved head and baggy robes. We follow past the rock garden, two dragons swirling together amidst white sand. Most impressive is the kitchen, everything familiar but built to an awesome scale. The blackened beams have seen thousands of meals, as have the clay rice cookers that can serve 200.

We move down the town's single street, past shops whose architecture goes back over a century. Some of them have lofts that now serve as cafes. It's refreshing, the lack of chain shops, flashy neon signs, or powerlines. The clouds are moving in and cooling the day, so we duck into the modern International Cafe run by a guy who speaks English and French. The cappucino I order from him gives me an intense rush, my body not having had strong caffeine for weeks. I had a similar equilibrium problem as I went cold turkey earlier in the walk, listing strongly left for three or four steps. It is a wonderful day, one where we don't have to get anywhere, and can let the hours fall away quietly, slowly...

On the turntable: Ricki Lee Jones, "Balm in Gilead"

On the nighttable: Edward Abbey, "Resist Much, Obey Little"

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Kumano Kōdō XVI

09/16/09

...it had rained all night but the morning was blue and clear. I looked out the window at the inlet just below, the tide dropping by the minute. In the bathroom, I noticed a small shrine to Fudo. He is the god of immovability, but the toilet is the one place where I most hope for movement to occur.